Palace of Justice

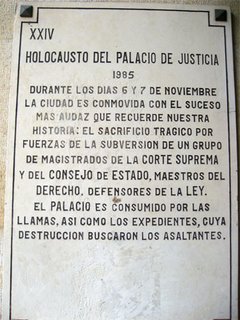

Our last meeting on Saturday was with a group of family members, along with their lawyers and other supporters of people who were killed or disappeared in the attack on the Palace of Justice. Twenty years ago, the M-19 guerrilla group launched an ill-fated attack on the palace. The military counterattacked, burning the building and killing in the process almost all of the judges, guerrillas, civilian workers, and visitors. Video clips show soldiers taking civilians whom they suspected of being guerrillas out of the building. Two of those were Carlos Augusto Rodriguez, the manager of the cafeteria, and Cristina, a friend who was replacing Carlos' wife Cecilia while she was on maternity leave. Even though the building was subsequently rebuilt, these civilians were never seen from again. We met with Cecilia, their daughter Alejandra who at the time of that attack was one month and six days old, Carlos' brother Cesar, Cristina's brother Sebastian, and others. The group recounted their struggles to find out what happened to their family members, and gave us details on the status of their case. They are pressing for sanctions against soldiers who carried out that attack, especially those who have taken posts in foreign embassies. So far, attempts to recover remains of the bodies have been unsuccessful. Alejandra made an emotional and moving statement:  More important than the remains of the bodies, we want to know what the soldiers did to them, to tell the truth about what happened. How could such important people get away with this? Will they be punished? More important than jail is to tell Colombia and the world what things they did. We want the truth. I don't care if they are set free, I want the truth. My friends don't know about the palace, or if they know something it is only that the guerrillas were bad. But they don't know the responsibility of the state. We need consciousness among the young of what happened. This could lead to social pressure to change the country. After the meeting, we toured a bit of the study. The rebuilt palace is at the same location as the old one, on Bogota's main Bolivar Square. Across the plaza on the city hall, plaques recount the city's history. The final plaque, #24, reads as follows:  Palace of Justice Holocaust 1985 During November 6 and 7, the city was moved with the most audacious events in our history: the tragic sacrifice by subversive forces of a group of Supreme Court justices and the Council of State, law professors, defenders of the law. The palace is consumed by flames, as well as court cases, whose destruction was the attacker's goal. That is the official version of these events, even though it was the military that attacked and burned the building with the judges and others inside. Some think that the military's goal was to destroy court evidence in the building that would link them to drug trafficking. The Colombian government continues to act with impunity in this and many other cases, and it is resolution of these issues that the family members, and many others in Colombia, seek.

Bombs

Yesterday we went to the Ministry of Defense that featured a United States Navy bomb in the lobby. We met with the Ministry’s viceminister Sergio Jaramillo. His take home message was to let the justice system do its work. The military, he emphasized, is doing a lot of human rights work and pressing for a more integrated approach to working with rural communities. From his point of view, the government was not perfect but going in the right direction and with time things would improve. We then met with Birgit Gerstenberg at the United Nations High Commission for Human Rights. They have just published a report on the current situation in Colombia. It concludes that “The right to life was affected by the persistence of murders, with the characteristics of extrajudicial executions, attributed to members of the security forces, particularly the army.” The number of human rights violations increased from 2005 to 2006, with Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities, social leaders, human rights defenders, peasants, women, children, labor union members, journalists, and displaced persons particularly affected. “High levels of impunity persist,” the report states. Gerstenberg noted that NGOs were not very confident in the attorney general’s office to solve these problems, and she also noted failings and shortcomings of the Law of Justice and Peace. They are dealing with more than 10,000 cases, which is perhaps ten times the number that they can handle. Nevertheless, she has faith in the attorney general’s office to pursue this process, even though it will take a long time. Truth, Gerstenberg said, is the most important. Colombia continues to register 3-4 cases of death or threats of death per day.

Thursday: Law of Justice and Peace

Again today we had two talks that gave fundamentally different visions of the Law of Justice and Peace designed to reintegrate demobilized paramilitaries into society. First we met with Jenny Claudia Almeida, a lawyer with the justice and peace section of the attorney general’s office. She painted a picture of a 40-year conflict in Colombia as a result of drug trafficking, with the paramilitary forming as a conservative reaction to left-wing guerrillas. The Law of Justice and Peace was promulgated one and a half years ago as Uribe’s attempt to find a political solution to the country’s conflict. Almeida emphasized that the law comes out of the will of the paramilitary to accept the law. Their punishment is relatively light (often 5 years in jail), but in exchange they must leave their armed group, come completely clean on their actions, and turn over their property. The attorney general’s office is constructing a massive database to document and verify paramilitary actions, and to cross check stories. Almeida gave a rather emotional presentation, stating that she was personally tired of death and the compromises of this law were worth it to have peace. Investigating these cases was like taking the lid off of a pot, as increasingly more information came out. Almeida was professional but also appeared passionately committed to her work, even while admitting that the law was politically motived by Uribe’s interests. We then met with Luis Jairo Ramírez who painted an entirely different image of this law. Rather than rooting the conflict in drug trafficking, which is a recent phenomenon, Ramírez traced it back to the Spanish conquest 500 years ago. A new cycle emerged in the 1940s with a consolidation of the dominate culture that excluded popular sectors, leading to the emergence of guerrilla groups to defend peasant interests. Paramilitaries emerged in the 1960s not as a third armed actor, but as an integral part of the state. Financed by drug trafficking, land owners, elite economic interests, and multinational corporations, the paramilitaries engaged in a dirty war. Paramilitary leaders claimed that they would disappear when the guerrillas did, but the recent history of demobilization with the guerrillas still in action casts doubt that this was the objective. Rather, paramilitary actions led to an extreme concentration of land ownership, in reality a reverse agrarian reform. Furthermore, their goal was to liquidate civilian opposition, in particular a genocidal war against union leaders. In contrast to Almeida, Ramírez painted the Law of Justice and Peace as a sham, as an amnesty to forgive crimes without requiring any serious punishment, reparations, or structural changes. It was a law of impunity. Furthermore, it was a misnomer to label this a peace process because peace is negotiated between adversaries and not among friends, as was the case with Uribe and the paramilitary that never attacked his government or economic interests. Ramírez called for a true peace agreement not so that everything stays the same, but so that things change.

Wednesday: Night and Day

If yesterday’s meetings provided differing views on the Colombian conflict, the two talks today were even more dramatic in their contrasts.  Early in the morning we flew from Apartadó to Medellín and proceeded to a meeting with the government of the department of Antioquia. We met with the Secretary of Government Jorge Mejía Martínez and Human Rights director Rocío Pineda. Antioquia’s government is allied with conservative president Alvaro Uribe, and they shared his negative views on the San Jose peace community. Mejía said that they want to open up communication with the community, but it has been very difficult because they isolate themselves. He said he respected their choice not to use governmental services (such as the school in the town of San Jose), but that it was an irrational decision. He justified the presence of police in the community because it has led to a drop in violence. More communities request police then they are able to provide, so San Jose should feel privileged to have the police station. Furthermore, Pineda added, there is no longer a need to engage in armed struggle as evidenced by ex-guerrillas capturing the mayoral post in Bogota and the governorship of Valle. People support Uribe because he has fulfilled his promises to rid the country of guerillas, even if it has meant sacrificing liberties. She emphasized that war has passed through Antioquia, and now peace is taking hold here. The meeting in the afternoon with three human rights lawyers could not have been more different. While the governmental human rights director seemed to be positioned to whitewash the crimes of the paramilitary violence, this group strongly criticized the Peace and Justice Law which demobilizes paramilitaries and provides them with political rights. The lawyers denounced it as an impunity law that ignores the rights of victims and provides no mechanisms for reparations or confessions. Leaders only acknowledge acts of complicity by soldiers who are already dead, and continue to maintain that their victims were guerrillas. The demobilization is a sham; the structures are the same but only the name of the organization has changed to Aguilas Negras. In contrast, the lawyers have launched a campaign to accompany victims of the violence and to bring truth to light. They call their campaign “Memories against silence and impunity: Never again crimes of the state.” Extrajudicial executions by the military continue, and claims that they have stopped are not credible. These lawyers see the military’s human rights language as pure rhetoric, nothing more. It is a lie that there are no more paramilitaries. Furthermore, in contrast to the contention of the governmental human rights officer a drop in homicides is not due to a police presence, but when the paramilitary gain hegemony they commit fewer crimes in order to project an image of peace and harmony.

Tuesday: Dominant classes

We spent Monday visiting with subalterns at San Josecito, and in contrast we spent Tuesday with the dominant sectors of society. It provides an interesting study in contrasts.  We started out the day with Lt. Colonel Hector Miguel Cruz Rocha of the National Police. The armed forces in Colombia have 4 branches: Army, Navy, Air Force, and Police. As a result, the police tend to be more militarized than in some countries, and their functions tend to blur with those of the army. They often coordinate activities, and to a casual observer even their uniforms appear to be similar. We were concerned about the police presence in the peace community San Jose de Apartado. The Lt. Colonel said that while they respect the community’s space, the armed forces have a right to be there. He bragged about the progress they had made in bringing people and social services into the community. A common problem they face are demobilized paramilitaries who turn to common criminal activities.  Our second meeting was with Colonel Jorge Arturo Salgado Restrepo who was second in command of the 17th brigade. Salgado had spent several years training in the United States, and spoke good English. He projected a smooth image of the Colombian military as a professional force with a strong concern for human rights and the concerns of the community. He spoke of this as a post-conflict period in which the feeling of sense of security in the zone has dramatically increased. After any combat operation, the military closes down the site for a civilian investigation. The Colonel spoke of concerns for legitimacy, and winning the hearts and minds of the people. He had a very positive image of Colombia.  Our third meeting was with the mayor José Phidalgo Banquero Zapata of the municipality of Apartado. While the police and military betrayed paternalistic attitudes toward the peace community, the mayoral staff’s attitudes bordered on condescending and disdain for their efforts. They were the most impoverished of the municipality’s four regions, and their resistance to social development programs meant that they lagged behind. It was for their own good to accept a police command post in the community. Before members of the peace community were not receptive to the municipality’s efforts, but now that they had left the has government brought in new inhabitants and life has improved in the urban center of San José. We received reports that documented a drop in homicides from 2004 through 2006, but a sharp jump again in the first two months of 2007. Although the municipality claims that the police presence has brought more security, and although it appears that most of the homicides are intrafraternal violence among paramilitary groups, the officials complained that only the guerrillas had not demobilized and were the source of the lingering problems. Three different dominant class visions of the problems facing San Jose de Apartado, and each of them radically different from the subaltern critiques of the rural farmers we visited the day before.

Monday: Part 2

We spent the day in San Josecito talking with community members. They described how rich the region is in natural resources–bananas, cacao, lumber, coal, water, etc. This leads to conflicts, with elites using military and paramilitary forces to displace poor farmers from their land. CSN has long worked with this community. Previously the military and paramilitary set up roadblocks between the village of San Jose and the city of Apartado, but now these armed forces remain more hidden. The leaders consider the situation to be more dangerous now, and feel as if it is building up to another massacre. Their faces carry the expression of being marked.  Beatriz is an artist who paints community scenes to describe their history and struggles. Community members are determined to stay and defend their land. Not only would it be hard to adapt to a new country with a different culture, Beatriz noted that they have an Indigenous heritage and want to remain where their roots are. They refuse to retreat, and are determined to continue to defend their land and rights. Beatriz related that people in the community have always said that San Jose will die standing rather than living on its knees.  At the end of the day we drove up to San Jose de Apartado which peace community members had abandoned 2 years ago after a massacre that killed community leader Luis Eduardo Guerra. The military then occupied the town, allegedly to protect it. The community that previously had prohibited all armed actors from entering is now crawling with soldiers and police. A sign at the entrance gives the seemingly contradictory message of "Welcome to San Jose de Apartado, Land of Peace - National Police." The community had outlawed alcohol, but now is full of bars as well as evangelical churches. It was eerie. We looked around and then quickly left. After 10 years of resistance the peace community has faced much suffering but also triumphs. They know that they will continue to face deaths and that at any moment they can be killed. But they defend the truth, and the memory, transparency, and clarity of martyrs like Luis Eduardo gives them the strength to continue. They are determined to fight until the last person, even as new seeds of resistance are born in the community. Since being displaced two years ago, nine children have been born. Even in the face of incredible repression, San Josecito has hope for the future.

Medellin

This morning we flew back from Apartado to Medellin. In Medellin, we had two meetings that were so very different from each other. I'll write more about them later. Then we did a quick run thru the local museum that features work by local artist Fernando Botero. Then it was off to the airport and quick flight to Bogota where we will spend the rest of our time here in Colombia.

more info later...

I wrote up a post about what we did today but some of the info might be a bit...well, I'll have someone else read it and post more info later--hopefully tomorrow. So, check back.

San Josecito de Apartado

This morning we arrived in Apartado from Medellin. On our way to breakfast, Cecilia commented that everything in this town seemed so normal, and that it would not be until we started to talk to people that we would have a sense of the awful things that have happened here. It reminded me of Rwanda which also seemed so normal for having experienced barely a decade earlier one of the worst genocides in history. This afternoon we arrived in our sister community, San Josecito de Apartado. Two young girls were laboring over a banner entitled “Lideres Victimas por el Estado.” By hand they were painting the names of all of the members of the community who had been killed by government forces. The list was extensive. Four to five people are killed daily in the municipality of Apartado. Eight have been killed in the last week. Right now many of the killings are between rival paramilitary gangs struggling for control over drug trafficking in the region. They kill people who testify against them, but also target human rights defenders and engage in “social cleansing” (killing of prostitutes, thieves, beggars). We return to our hotel in the city of Apartado for the night, and will return to the rural village of San Josecito tomorrow to continue our discussions.

Medellin

Arrived in Medellin last nite. Up early for flight to Apartado, where our program starts.

Colombia Support Network

I am traveling with the Colombia Support Network to Medellín, Apartado, and Bogotá from March 10-18, 2007.

| Marc Becker's Home Page

| marc@yachana.org |

|