Acteal and Las Abejas

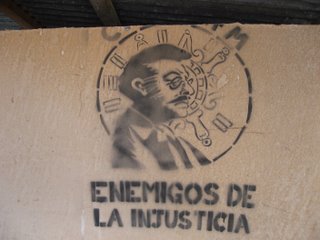

Ten years ago I taught Mexican history for the first time at Illinois State University and wanted to travel to Mexico to learn a bit more about the country so that I could better teach the subject. We arrived with a Schools for Chiapas delegation to Oventic barely a week after a brutal massacre of 45 pacifist Abejas (Bees) at Acteal. That was a powerful and troubling experience, leading us to return in 2000 with Tomás on a Cloudforest delegation for the third-year anniversary of the December 22 massacre. That experience was also so powerful, that I thought I would return every couple years for the anniversary. It is hard to believe that it has been almost seven years since I was in the community. It was good to be back. Whereas Zapatistas talked about “compañeras y compañeros,” Abeja leaders welcomed us as “hermanas y hermanos” to the “tierra sagrada de los martires de Acteal. Diego Pérez Jímenez, the president of the board of directors of the Bees, gave us a brief history of the organization since its founding in 1992. The organization has its roots in a land conflict with PRIistas and grew into ambushes between the two sides that left one of their leaders dead. Without an investigation, the government took five of them into custody. They began to organize to gain their freedom, and marched on San Cristóbal to demand their freedom. The march did not have a name, and they began to look for one: ant, butterfly, but finally they settled on the Bees because bees have a Queen, produce honey, look for flowers and water, and always come back to the hive. We also work like this, Diego said. Through the march, pilgrimage, and prayer, they were able to gain their freedom. The civil society organization Las Abejas was born.  Vice president Miguel Hernando Vasquez explained how Las Abejas were founded as a result of injustice and the violation of human rights. The organization was not created without reason, and given the lingering conflict the organization still has a role to play. Not all of the paramilitaries from the December 22, 1997 massacre have been captured, and more importantly the intellectual authors of the crime have not been identified. They face continued rumors that the paramilitary group will return, and that they still have arms hidden in caves to kill us. Miguel called for justice for the community and the world, but declared their determination to continue in a peaceful struggle. We won’t lose our road, he emphasized. We won’t use arms. We will continue the struggle through the word of god, prayer, and fasting. We are not alone; we draw on the strength of god.. Diego continued that they were always living with threats from paramilitary groups and the military. They have asked the government to demilitarize the area, but they have not done so. Both the military and paramilitary come through here on a daily basis. They continue the struggle so as not to lose force. They gain strength from the thousands of visitors to the community. Even though they suffer, they will continue the struggle and continue to ask for peace and justice–not just here but throughout the entire world. Diego concluded by inviting us to return in December for the tenth anniversary of the massacre and the fifteenth anniversary of the founding of the Bees. They are planning a huge celebration, and indeed it is very tempting to return.  After the meeting with the Abeja board, we visited the community of El Nueva Paraiso who had been displaced from their home community of San Clemente where 27 families lived on 147 hectares of land. Almost eight years ago they had left San Clemente for Pantelhó before finally buying 8.5 hectares of land this April at their current site. Community representative Manuel directed the conversation, and translated other community members’ comments from their native Tzotzil into Spanish. At first the men dressed in western clothes and wearing rubber boots common in the campo spoke, and when they were done barefoot women in traditional-style dress took their turn. It was one of the rare times in Chiapas that women addressed us, though the entire conversation was mediated through Manuel. It was unclear whether he was the only one with strong Spanish skills, or whether he preferred it this way so as to control and direct the discussion. Typical of Indigenous narratives, the stories were often less than linear or chronological and somewhat repetitive but also often painful as community members recalled their difficult history.  Antonio began with telling us how the community joined Las Abejas when they faced arrest warrants. They were not guilty, but were afraid. Lucas told us how Juan Jimenez arrived in San Clemente to escape a murder charge in Pantelhó and began to extort payment from community members. His thugs could not properly be termed a paramilitary group because they did not have visible contact with the police, but they did work together. Mariano explained how in 1999, Juan Jimenez had demanded 850 pesos from each family that they paid, but when he began to demand yet more money they could not afford it and were forced to leave for Pantelhó where 17 families lived in 10 small houses. Sebastian told how they had borrowed the money against their coffee harvest, and that Juan Jimenez wanted the money to buy two of his brothers out of prison. Miguel said that when community members said they did not have the money Juan Jimenez’s henchmen grabbed and beat Diego. Antonio Luna “el viejo” said that he talked to the mayor who said he would talk to Juan Jimenez to stop the abuse, but when the mayor did nothing the community was left without any legal recourse.  Now it was the women’s turn to speak, and Juana said that although they struggled for justice they received no help from the government. María and Rosa explained that they could not get justice because of Juan Jimenez’s links with the government. Finally, the group left San Clemente with support from the Zapatistas. As refugees in Pantelhó, the men could not get jobs and the entire group suffered. Women went to work as servants in the houses of mestizos where they faced long days with low pay. Katarina said that a French parish priest in Chenalhó helped them out. María said that with the arrival of observers they brought money to help buy the current plot of land on which they live. Margarita said that now that they have wood to cook, and they are happy to be here. Manuel explained the year-long process of finding the land and pulling together the funds to buy it, and the support of Dr. Raimundo at CEDECI to survey the plot. Now they have the title for the land. But they still hear gunfire at night, which makes them uneasy. They like having observers in the community because they feel safer. Juan Jimenez wants to come kill the Abejas, but it is harder when observers are present. It is important to show that we have contact with others, Manuel emphasized. They do not receive help from the Zapatistas because they are engaged in different struggles. “We are pacifists,” he emphasized. “We ask for justice only with words.”  I had forgotten how beautiful the mountains in Chiapas were, and I found the rock outcroppings above the aptly named El Nuevo Paraiso particularly stunning. As the van wound its way on the dusty gravel road up the hill I struggled to get a picture of the rocks out of the window. Below we could see the clear outline of the community. After only 3 months the high population density on the small plot was already denuding the land compared to the lush surrounding mountains. I handed my camera to Walt who promptly took a picture of a tree instead. While the Zapatista communities with which we met maintained their proud determination to break bonds of dependency and remain autonomous from the government, those at El Nuevo Paraiso openly welcomed donations and external assistance–and in fact seemed to be dependent on such aid. Delegation members responded in kind. A proud but broken people? For me, it was one of the most disheartening meetings.

Mesa Redonda: Ecuentro entre campesin@s del mundo. Frente al despojo capitalista. Defendamos la tierra y el territorio

As part of the Zapatista Encuentro, they planned two roundtables on the defense of land and territory–one last week in Mexico City and another one in San Cristóbal on the eve of the start of the Encuentro at Oventic. The idea was to create a dialogue around peasant and Indigenous movements around the world. Representatives of rural struggles in India, South Korea, Brazil, USA, and Mexico were present on the roundtable. Those from outside the country were given 30 minutes to present their concerns, while the Zapatistas spoke for about 15 minutes each. The representative from India (sorry I don’t have names) gave an overview of the country’s agricultural crisis that resulted in a high suicide rate. People, the speaker emphasized, will not give up without a fight. The only way to win is to fight together, otherwise we become slaves.  The Korean representative framed his discussion as part of a history of foreign intervention and peasant struggles. In order to stave off a peasant revolt, the king invited Japanese intervention and the peasants became slaves and the country become a colony of Japan. In the post-war period, this history repeated itself with the intervention of the US and USSR. The peasant struggle becomes one against imperialism and neoliberalism. Peasants needed to unify with workers because it is not possible to win alone. Sonia Soriano (sp?), the secretary of gender in the national directorate of the Landless Workers Movement (MST) in Brazil, discussed the country’s divided left and feelings of deception with Lula. Rural workers found it difficult to work with city dwellers, but she emphasized the importance of building alliances in order to succeed in their struggle for agrarian reform. She criticized ethanol projects that required 4 liters of water to produce one liter of ethanol. With the burning of cane sugar that closed nearby schools, ethanol production was hardly so clean. Soriano emphasized the need to be optimistic as they looked for new roads to create new cycles for the left. George Naylor, president of the National Family Farm Coalition in the US, began his presentation of a discussion of how agricultural production in his home state of Ohio is increasingly moving to a monoculture economy of corn and soybeans. This leads to a destruction of biodiversity that worsens with NAFTA and the WTO. Commodity prices are temporarily a bit better because of ethanol production, but this is not a longterm solution. Family farming is almost dead in the US, with an increasingly smaller number of large agro-businesses creating the majority of the country’s agricultural production. We have lived the market economy, and it does not work. Naylor concluded that we have much to learn from the Zapatistas about democracy, the environment, and human values.  After 2 hours, it was finally time for the Zapatista leaders to give their presentations. As the noisy audience quieted down, it become clear who the largely white European and North American participants had come to see. First, EZLN Comandante Tacho gave space to an Indigenous delegate from Venezuela to denounce Chavez’s plane to mine coal on their land and to draft a new Indigenous law. Tacho then discussed the essential importance of land and territory to Indigenous struggles since the 1910 Zapatista uprising that demanded deliverance of land to those who work it. Indigenous peoples never hurt mother earth; we take care of it and do not treat it as a commodity. Although Bishop Samuel Ruiz and the church came to their aid, their situation has only become worse. Lieutenant Colonel Moises then discussed the problems with Mexico’s educational system. Zapatista schools and health promoters work. Moises repeatedly emphasized the need to take control over the means of production. We need to challenge the capitalist system, and to do so we need to put the means of production in our hands. To be anti-capitalist means to take factories and lands out of the hands of capitalists and to put them in the hands of workers and peasants. Through the process of “tomar, quitar, recuperar” (occupy, take, reoccupy), we can challenge savage capitalism.  Finally, it was time for Subcomandante Marcos to take the mike. After seeing Fidel Castro, Hugo Chavez, and Evo Morales, Marcos was the last major living revolutionary leader who I had wanted to see in action. We had been sitting outside of the little church at CEDECI where the talk took place listening to the talks over loudspeakers, with me sticking my camera thru a window to take pictures of the speakers before returning to my seat. With Marcos, I was left with a choice: move to the loudspeaker in an attempt to get a higher quality recording for WORT or leave the I-River and try to squeeze into the increasingly occupied window spaces to get yet another blurry photo of the Sup. I deeply regretted not arriving early enough to get a seat in the church, or to squeeze in as Gwen had done to be able to observe the spectacle in person. In the end, I opted for a clear recording that hopefully the compañer@s at WORT will be able to use for En Nuestro Patio. So I heard, but did not see.  Marcos is older and fatter than he was when he first went into the jungle 20 years ago, but his style is still as poetic and beautiful as it was when he first burst on to the public stage on January 1, 1994. It was also almost impossible for me to understand what he was saying. I felt better when later my colleagues listening to the English translations on their portable devices told me that the interpreters were likewise having an impossible time with the talk. He told two stories–the first something about a can of Coke and anti-capitalist consumption, and then other something about the history of a transsexual who preferred the term compañeroa. Marcos also mentioned the Maya use of “we” instead of “I,” and echoed Moises’ emphasis on the need to struggle together to gain control over the means of production. The problem is that few own much, and many own nothing. We can change this by attacking the means of production. He called Bush a Burro, called for liberty and justice for Atenco and Oaxaca, and referred to worlds without a name.

Chamula

San Juan Batista de Chamula has a reputation for being a conflictive and intolerant place, tho with an interesting syncretic religious culture. When I said I wanted to go on my last orphaned day in San Cristóbal, Tomas and Carolina responded with a rather strong "Do not take photos!" I wonder if I had entered the town with no awareness of its history and reputation whether I would have seen it as little different than any other Indigenous town. We go expecting a rather rough and gruff reception, and that is what we get. The cathedral is in the middle of town and its main attraction, and the man at the door informs us that we need to go to the tourist office to buy 15-peso tickets to enter. The man in the tourist office sells us tickets with hardly saying a word. Inside the cathedral on a bed of pine needles with hundreds of candles, tourists gather around a traditional healer to watch as she treats a man with alcohol, tobacco, and a chicken. We are not allowed to take pictures, but the presence of paying tourists seems to turn this into a commodified spectacle. Outside the cathedral, a tourist attempts to take a picture of a religious procession but angry officials in traditional dress scream and run at her as if to beat her with their staffs. Then then turn on another man who apparently took a picture with a cellphone and chase him around to the back of the municipal building where they lock him in a cell. Had we not known the history of this community, we would have been quite shocked by this vigilante justice. As is, it just seemed to confirm for us the image of the community's reputation.  In the late afternoon we climbed the hill to the San Cristóbal church. Fireworks have been celebrating the town's patron saint. This morning a long parade of cars decked out with balloons and honking their horns crowded the city center. At the back side of the church, a priest was blessing a seemingly endless line of cars with holy water. Police officers directed traffic, and tried to hurry up those who lagged behind. The priest went thru the motions seemingly mechanically after hours of this work, with two young girls in tow carrying a collection plate for donations and a plastic jug of holy water. Rain had been threatening all afternoon, and finally it began to sprinkle and chased us back to the house. And so Chiapas comes to an end, and I head back home tomorrow. I'll try to write up the rest of my notes on the plane on the events of the last couple days.

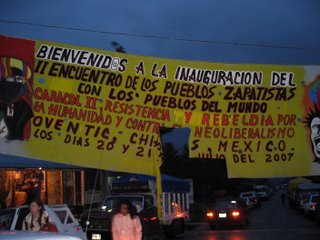

Encuentro Zapatista con los pueblos del mundo

Yesterday we traveled to the Caracol of Oventic for the Zapatista meeting with the peoples of the world. For me it was an anticlimactic culmination of my time in Mexico. Attending the planning meetings for the next Zapatista intergalactica was my main purpose for coming to Mexico this summer, and we were only there for a couple hours for which will be a week-long series of discussions and meetings. The Encuentro had started the day before, but our leaders thought it would start slow and late so we went to Acteal instead (I’ll write more about that later). We were supposed to go to Magdalena de la Paz today for their annual feast day, but we stopped there yesterday morning on the way out to Oventic so we would not have to make a separate trip today, which meant even less time at the Encuentro. It appears that all that will happen today is a caravan from Oventic to Morelia where the meetings will continue, and as I am leaving early tomorrow morning there is little purpose in going on that ride. So, the delegation ends a day earlier than planned and I am left in San Cristóbal with little to do but be a tourist–which was not at all the purpose of this trip.  We arrived in time for the fifth plenary on women, which turned out to be rather flat and predictable. Guillermo coordinated the table, Comandanta Lorenza gave the welcome, and Lora read a statement that she had written with María Luisa and Verónica on the issues that women faced in Zapatista communities. Women, she read, were mistreated, ignored, forgotten. The Bad Government treated women as if they served no purpose except to have kids and take care of animals. But that is not true–they are capable. At first there were few women in charge of community responsibilities, and there is need for more formation and training so that women can do more work. Women will continue working with health care, education, in the community, security, and with natural resources. But women cannot travel alone for fear that they will be raped. Men look at us in a negative light when we work, but we cannot give up.  The audience, largely made up of young white anarchist activists from Europe and the United States, was then given 15 minutes to ask questions. Most of the questions were hardly probing, and received short trite answers. Are there programs for domestic violence? Elsewhere, but not here. How are men who abuse women punished? By autonomous municipal authorities. In Zapatista communities there is always justice. How do you prevent domestic violence? Women have to understand their rights, and men need to respect women; thru education. They said that the comandancia has declared that women have full rights to participate in the Zapatista organization. Some men try to help out, but very few of them make tortillas.  After a two-hour lunch break we then moved on to the sixth plenary on collective work. Comandanta Florencia lead the table, and Paulina read a statement prepared by her, Daniela, and Juan Manuel. The presentation began with a discussion of coffee and a lack of agricultural land. They often have to sell artisan crafts cheaply. So the women formed a cooperative to work together in search of solutions. They do not receive any support from the Bad Government. They have problem accessing national and international markets, and can’t sell everything in their coop stores so they have to sell the rest in private shops at a low price. Only the rich and government are free to export the richness of the country. Furthermore, the Bad Government looks for ways to divide people and block us. People who are not Zapatistas use our name to sell stuff and make money off of us. We take advantage of participating in the Zapatista struggle to avoid what we have suffered for years, and we still lack a lot for Indigenous women to be complete. Juan Manuel then added some additional comments about attempts to organize coffee cooperatives to sell their produce at a better price rather than through coyotes. This was then followed by more stupid questions and trite answers.  As the hot afternoon sun beat down on us, the seventh plenary addressed the issue of the organization of communities. We moved straight into the eighth plenary on autonomy as rain clouds built up in the west and moved over Oventic. Under a cold rain, we heard about Indigenous forms of government that were completely different from western models. Zapatistas declared their rights of autonomy and free determination. We need to capture power from corrupt political parties and the rich in order to solve our own problems, rather than letting them divide and conquer Indigenous peoples. By this time, it was raining harder so they moved the talk into the auditorium, and Tomás gave us a ride back into town.

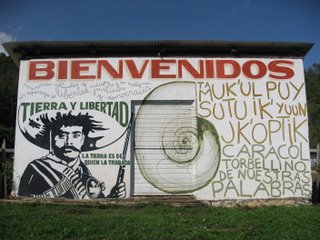

Caracol Morelia

We drove three hours out past Ocosingo and Altamirano to the Caracol of Morelia to request permission to visit the autonomous Zapatista municipality of Olga Isabel. We waited outside the gate of the Caracol for the security team to give us permission to enter, and then waited for hours more under a tree for the Junta de Buen Gobierno to receive us. We then had a short visit with the Junta before continuing on to Olga Isabel. With a dinner stop in Ocosingo, we arrived well after dark with the community leaders already asleep. They graciously allowed us, however, to spend the nite in the community’s school. In the Caracol of Morelia, three men and women from the Junta de Buen Gobierno related to us their history and the struggles they still face. In 1994 at the time of the Zapatista uprising, they recaptured their land from surrounding haciendas. Now the government tries to provoke confrontations between Indigenous communities so as to try to defeat their struggles. But they vowed not to give up, and to continue fighting to control their land. They asked us to work together to change the neo-liberal capitalist system, to break the control of the capitalist elite. They can’t destroy us. We need to create one force, to form one big struggle.  At Olga Isabel, we first talked to two health promoters and then a council member. Their community was comprised of ejido land taken over by big ranchers. In August 1994, in the aftermath of the January uprising, they affiliated with the Zapatistas and re-occupied the land. They had faced threats, but these were never acted on so they were able to remain on their land. Before the community relied on the government for health and education, but now they do it themselves. They don’t charge for consultations at the health clinic, but a bit for medicine to cover their costs. They emphasize preventive measures: boiling water, sterilizing it with chlorine, using a latrine, eliminating garbage, emptying puddles where insects can breed, and fence off animals. Council member Antonio filled us in on the history of the communities conflicts with the Coordinadora Nacional de Pueblos Indios (CNPI) and the Organización para la Defensa de Derechos Indígenas y Campesinos (OPDDIC) over land titles and whether to accept government resources. The Zapatistas refuse to be dependent on the government, including paying for or receiving services from the government, while the others want to take advantage of the government’s offer to grant legal land titles. Part of the occupied land has been legally formed into the Ejido Mukulum, and the second part that is Olga Isabel is currently in front of the agricultural tribunal. Morelia’s Junta de Buen Gobierno has decided that if the tribunal rules against the autonomous community they will not leave the land. Since the Congress refused to implement the San Andrés Accords the Zapatistas have not been in dialogue with the government and see little reason to do so. Several former Zapatistas have gone over to opposition groups, and since they know the people and structure of the autonomous community so well they create may problems. From the Zapatistas’ perspective, the government is deceiving people which leads them to leave the organization. Antonio in particular has been the target of strong and direct threats. The police constantly pass by on the road and take pictures of the community. Current PRD governor Juan Sabines does not want to remove the Zapatistas from their lands, which has brought a certain amount of calm to the community. Antonio expressed his gratitude for our presence in the community, and asked us to continue our visits and to tell the world the truth about what is happening there. What they have is not perfect, Antonio conceded, but they are committed to building on their efforts in health, education, and production. Activists in the community, however, seemed to be exhausted from the constant struggle.

San Cristóbal de las Casas

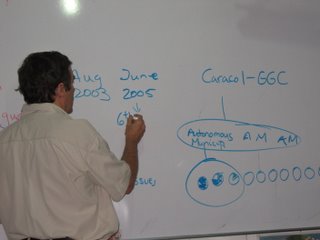

On our first day of the delegation in Chiapas we had three meetings in the city of San Cristóbal de las Casas. The first one was with Rafael Pérez Gutiérrez at the CEDECI (Centro Indígena de Capacitación Integral Fray Bartolomé de las Casas) that for almost 20 years has worked to open autonomous training spaces for young Indigenous peoples. The focus is not only on learning but also on personal formation. It is an informal center, without rigid rules. A short term goal is to provide career opportunities, but a broader objective is to create a new Chiapas. This is engaged not only on the level of theory, but also practice. The center also engages underlying issues of racism and unemployment. CEDECI is on a 20-hectare campus on the edge of town. They began building the campus three years ago, and construction is still in full swing. It is broken into different areas of technical training, food preparation, and agriculture.  In the afternoon, we visited with SIPAZ (Servicio Internacional para la Paz) that works on dialogue and peace issues in Chiapas. Team members Jet, Tania, and Jon gave us an overview of the history of conflict in Chiapas and a summation of SIPAZ’s work. Three factors of poverty, Indigeneity, and marginality interact to reinforce each other. They described Chiapas as a rich state with great inequality, and festering with poverty and extreme poverty. They described divided communities, with Acteal (for example) divided into Zapatista, Abeja, and PRI parts. They presented this as part of a strategy of divide and conquer. In 2003, the Zapatistas transformed their 5 Aguascalientes that were spaces of encounter between the Zapatistas and civil society into Caracoles or shells, so named because of the spiral inward and a shell used to call meetings. Juntas de Buen Gobierno (Good Government Councils) were formed in each community to coordinate their work. In 2005, the Zapatistas presented their Sixth Declaration that called for anti-capitalist alliances to build a new system. This led to “The Other Campaign” in opposition to the standard electoral process that led to the election of Felipe Calderón on July 2 of last year. Since 1995, SIPAZ has worked as an observer mission in Chiapas around three main concerns: international presence and accompaniment; information and lobbying; and peace promotion.  In the evening, we met with Miguel Pickard from CIEPAC, the Centro de Investigaciones Económicas y Políticas de Acción Comunitaria. CIEPAC fills a need for providing information and analysis for grassroots communities and popular movements in Chiapas. They produce popular education materials, including books, pamphlets, and videos. Miguel laid out the recent history of the Zapatistas forming Caracoles in 2003 in order to return power and authority from the EZLN’s military structure to its civilian base. With the 2005 Sixth Declaration, the Zapatistas sought to consolidate their model of autonomy and to inspire others to reflect on what they could do in their own communities. The Zapatistas launched The Other Campaign under the assumption that the leftist PRD candidate AMLO would win the presidential elections last July, but when fraud brought conservative PAN candidate Felipe Calderón to power repression increased significantly against popular movements. Miguel pointed to an increased militarization of society, including the use of rape as a tool of control. He saw this government who usually resorted to tactics of buying people off rather than engaging in this level of repression. As doors close to peaceful protest, more armed groups begin to emerge. The left is divided, demoralized, and in tatters. Miguel painted a dismal picture of it being unclear where the Zapatistas or the left in general should turn, and what the future might hold for popular movements. Go to http://picasaweb.google.com/marcbecker2/Chiapas for my pictures.

Isthmus of Tehuantepec

We spent the last two days in Oaxaca on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the narrowest part of Mexico which historically has been a transhipment point between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean and currently is a focus of the Plan Puebla Panama (Putumayo). On Friday, we met with opponents to the Bénito Juárez hydro-electric dam project at Santa María Jalapa de Marqués, and on Saturday with opponents to La Venta wind farm project. The meetings left several of us feeling a bit uncertain about these groups and their agendas. We saw a definite rub between an environmentalist agenda and local concerns and interests. But is there more here than NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) politics wrapped in anti-neoliberal discourse? We needed a longer and deeper conversation to gain a fuller understanding of these organizations. In 1955, the Mexican federation government began surveys to dam the confluence of the Tequisistlan and Tehuantepec rivers in order to create a reservoir to irrigate the Isthmus. The Bénito Juárez dam that was built from 1956-1960 flooded the town of Jalapa, whose inhabitants were moved to the community’s current location in 1961. The community felt that they had received the short end of the deal and that the government had not fulfilled many of its promises. Their new lands were not nearly as fertile as the river bottom land that they had lost, and the government did not deliver on their promises of a new, modern town. Many former farmers turned to fishing in the new lake behind the dam. The group complained about a lack of consultation with the affected communities, that corrupt officials were the only ones who benefitted from the project.  With the dam now at the end of its useful life spam, the government is considering converting it into a hydro electric project. Given the history of experience with the current dam, the community is naturally suspicious of how this project will play out and whether it will have more negative impacts on their lives including their new fishing livelihood. The government promises lots of jobs with the new dam, but the community suspects that there will only be short-term unskilled labor while the dam is built and then a couple engineers will remain to run it. Community leaders asked for our solidarity in organizing against the neoliberal project that will benefit others but not the people of Santa María Jalapa de Marqués. On Saturday, we met with UCIZONI (the Union of Indigenous Communities of the Northern Isthmus Zone) that is organizing opposition to a wind farm at the appropriately named town of La Venta. Leader Carlos Beas Torres began with a presentation of how the Isthmus historically has been an area of contested geo-political control, and increasing United States control in the twentieth century. The Plan Puebla Panama (PPP) brought new mega-projects to the Isthmus and privatized local resources. Beas referred to this as a new invasion of investments that continue a history of extraction of wealth from the region. Although the PPP no longer receives the media attention that it once did, the project to connect raw materials with a global market to the benefit of multinational corporations rather than local inhabitants continues continued unabated.  Both the Bénito Juárez hydroelectric and the La Venta wind farm projects are part of this development. Studies show that La Venta has some of the best winds in the world, with constant steady winds of 9 to 14 meters per second while most places only have 2 to 5 mps. While the community sees the wind as normal, capital sees it as money. A problem similar to the Bénito Juárez dam project is a lack of information and consultation with local community members. In 1994, a pilot project set up seven windmills and in 2006 this was expanded with 98 more windmills, and now there is a plan to set up 88 more. A Spanish company set up the windmills, but pay very low rents for the use of the land. Community members are also concerned about the potential environmental impacts of the windmills, especially on migratory bird populations. Beas in particular presented his opposition to the wind project in terms of a global struggle against neoliberal capitalism that undermines local sovereignty. The government wants to fund foreign capital intensive projects, but does little for local sustainable projects. The government wants to depend more on remittances from migrant workers to the States than on developing local economies.  While UCIZONI received support from international environmental groups such as Greenpeace when they opposed a shrimp farm project, they receive no such support for their opposition to clean energy projects. Signs on the windmill project advertise that they are bringing renewable energy to Mexico. It is hard to oppose such a project. But what does one do when this project is part of a privatization of natural resources without paying attention to the needs and concerns of local communities? Isn’t this part of the problem of capitalism, that it is based on a culture of consumption rather than sustainable survival? While clean, these projects are not about local sovereignty and development. We come away with many questions, but as I write this we are about ready to start the Chiapas part of our program. We would need more time to make sense of our experience there, and what we should do with it.

Palenque

A break btwn the Oaxaca and Chiapas delegations, so I made a quick trip to Palenque. It´s the last major archaeological site in the Americas that I had yet to visit and I was looking for an opportunity to come here, and I´m glad I made the trip (even tho my bus from San Cristobal was 3 hrs late last nite). The first time I came to Mexico about 25 years ago I went to Teotihuacan and was completely enamored with that archaeological site. After that I visited as many archaeological sites as I could, and for a while wanted to be an archaeologist. It seemed to provide such a direct view into the distant past. But then in grad school I took classes with John Hoopes and he began to show me these sites in a completely different light. Sites like Teotihucan are largely fabricated reconstructions. Furthermore, from a social history perspective, large sites like this focus on a small faction of elite society and ignore the masses. Much more important and interesting archaeological studies are done at sites that are not so much to look at.  In John Sayles´ film Men With Guns, a boy tells tourists bloody stories about the Maya so they tip him better. Tour guides seem often to be like that. I heard one tour guide on the site say ¨Los maya no era politica, era religiosa¨ (The Maya were not political; they were religious¨). Here we are at a site that focuses on a society with deep class divisions, with the elite controlling the labor of the masses to build these temples that served little purpose for the subaltern classes, and there is no political dimension to this site? So, I forgo the tour guide and wander around the site on my own until the heat begins to get to me. If I want more, I´ll go back home and review my notes from John Hoopes´ archeology classes. I've uploaded a bunch of photos to http://picasaweb.google.com/marcbecker2/Palenque.

Sergio Beltrán, UniTierra

The Universidad de la Tierra (UniTierra) was created as an alternative to formal education and as a space for free learning. There is no fixed curriculum or teachers, and control is in the hand of the learners. The institute is set up with 5 branches: alternative technologies, appropriate agriculture, popular communication and media, alternative medicines, and alternative research on social science.  We met with Sergio Beltrán who is one of 5 or 6 staff members at UniTierra. He talked about the history of recent social struggles in Oaxaca and showed us some video clips of struggles of these events that they had made. When the women took over the Channel 9 TV station on August 1 of last year, they called UniTierra to help with video production. Sergio talked about how taking over this station broke the image of a passive woman. He quoted Ricardo Flores Magón: “Cuando una mujer avanca, no hay hombre que se detenga” (when a woman is advancing, no man can stop her). We asked Sergio about the recent EPR attacks on oil pipelines that have been so much in the news while we were in Oaxaca but none of the groups we met with mentioned. He expressed his suspicions that the EPR was not a real guerrilla group but a shame to cover for government abuse, because they only seemed to attack when distracting media attention from a recent scandal would only seem to benefit the government.

Padre Manuel Arias Montes

Padre Manuel Arias Montes is the parish priest in the Jukilita neighborhood of Oaxaca. He explained two competing visions for the role of the church: one from above, and another from below. Arias always wanted to be with the people, and identifies with the popular church that approaches social issues from a community perspective. This work began 30 years ago with the arrival of Archbishop Bartolomé Carrasco in Oaxaca who put the church in favor of the poor and Indigenous peoples. Arias recounted a long history of exploitation and repression that people faced, with the government propagating systems of corruption and impunity. Governments become the worst caciques (chiefs) who take advantage of community members. Arias painted a history that depicted the church as responsible for launching social struggles in Oaxaca, including training teachers and Indigenous leaders and Christian Base Communities. Often, however, the church hierarchy betrayed these struggles and abandoned people to repressive forces. This situation finally exploded on June 14, 2006 with mass protests in Oaxaca. The government responded with repression rather than dealing with the underlying social problems. Arias said that the church was the first one to come to the aid and support of the striking teachers. Priests built solidarity by making statements in support of APPO and bringing food to the strikers, even as the church hierarchy allied with the repressive government. The hierarchy showed a negative face of the church. Nevertheless, Arias and other parish priests continue to be determined to work with civil society to make important fundamental social changes. Arias embraces the importance of Indigenous spirituality in his work, and points to the importance of Indigenous cosmologies to find solutions to problems that they face. Our meeting took place in a creation chapel that was decorated with a Mixteca symbol of tree of life that grew out of a sacred cave where god blew life into women and men. Arias also pointed to the important role of women, and what he termed the feminine face of the church and civil society struggles. He said that if priests maintain their authoritarian role they will remain alone, and women will continue with the more important work. Arias also said that at first the left attacked the church and especially the bishops for the stances that they took, but now the church has better relations with the left. The church’s more reflective stances also help strengthen class struggles.

San Cristobal de las Casas

Spent the last 2 days traveling thru the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and the leftist mecca of Juchitan, but haven't had time or Internet access to upload reports. Will do that tomorrow. Just arrived in San Cristobal de las Casas in Chiapas--tired and ready to go to sleep. Tomorrow afternoon I'm going to Palenque, and then on Tuesday the program starts here. More soon.

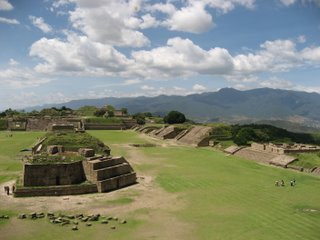

Monte Alban

This afternoon we went to the Monte Alban archaeological site. I got too much sun and now my head hurts. It was a fun day out there, however. Photos at http://picasaweb.google.com/marcbecker2/MonteAlban. This morning we visited with Father Manuel Arias Montes of the Jukilita parish, and this evening with Sergio Beltrán of the Universidad de la Tierra. I'll write up and post notes about that later. Two nites ago I had the pleasant surprise to run into Peter Herlihy who is in Oaxaca working on a participatory Indigenous mapping project. It was horribly tempting to travel with him and his crew to visit the project site, but in the end decided to stay with our delegation. Information on his project is at http://web.ku.edu/~mexind/.

Coordinadora de Mujeres Primero de Agosto

We met with Estela Río Gonzalez and Itandehuí Santiago Galicia of the Coordinadora de Mujeres Primero de Agosto. They told us their history of taking over the state TV and radio station last year in the aftermath of the APPO protests against Ulisis Ruiz (URO). The Coordinadora emerged out of a group of women who decided to support the striking teachers, and realized that they needed to organize themselves to achieve their objectives. Copying protests in Argentina and Chile, they rejected their traditional domestic roles and instead carried out a march of banging on pots and pans. They expected a couple thousand women to join them, but 15,000 showed up for a march on government buildings. With this momentum, they seized 28 buses to travel from the Zocalo to take over the state TV and radio stations. Originally the women only demanded 30 minutes on air to present their demands, arguing that as a state-run radio they had a right to have their voices heard. When the station refused this request, they took over the station. They decided that having men join them would be too provocative, so only women entered. Men remained outside as guards. The women deliberately chose to be respectful and not to destroy anything. No one knew how to use the equipment, so they had to coerce the technicians “with cariño” (with love) to show them how to run the station. For the first day the women did not eat or sleep as they ran the station. Long lines of women wanted to go on the air to talk and express their demands. As the occupation drug on, people brought food to the station. Husbands asked when they were coming home to take care of their houses, but the women said that the men would need to learn how to take care of themselves. Estela noted the problem of hard-headed and machista men, but their actions showed that women could do a lot. The broadcasts lasted from August 1 to August 21 when the government destroyed the station’s antenna to knock it off the air. The occupation remained until October 28 to care for the station so that they would not be accused to destroying the equipment.  Estela emphasized that this occupation demonstrated that women can do more than be in the kitchen. They demanded justice, and lost fear of repression. Itandehuí noted how she was impressed with the initiative shown by young women. People were surprised to see women able to run the station. “The job was not easy,” Itandehuí stated. The women were well aware of the repercussions of attacking a state institution. But they grew stronger as they went along. Out of this occupation, the women decided to form a broad, inclusive, popular assembly of women. Their demands were to free the political prisoners from the summer protests, and to address the issues of disappeared and tortured protesters. More broadly, they dream of a better world without poverty in which the government works for the people and for freedom and justice rather than enriching politicians. They want schools, hospitals, and funding for education. Itandehuí also pointed to the importance of including Indigenous women in the struggle since they are the most oppressed.

CMPIO

We met with three leaders of CMPIO, the Oaxacan Coalition of Indigenous Teachers and Promoters. Juan Santiago Santiago began with a history of how CMPIO emerged as part of a struggle to bring attention to Indigenous values and social issues in the educational process. In 1974, 350 Indigenous teachers and promoters went on strike to demand their rights, including a bilingual educational training center. In 1982, they introduced a special anthropology course to study Indigenous cultures in Oaxaca. Beatriz Gutiérrez, secretary-general of CMPIO, explained how CMPIO worked independently from its founding in 1974 until 1982 when they joined Section 22 of the teachers union that had been founded two years earlier. With Section 22, they worked more on pedagogical issues, but always with an eye toward joining social movements in communities to struggle against discrimination and to build better lives.  Fernando Soberanes explained how CMPIO broke with earlier programs that sought to integrate Indigenous peoples into the dominant Hispanic culture. Through the influence of Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy, they struggled to have the educational process match their Indigenous students’ realities. In 1978, CMPIO took over the Ministry of Education in Mexico City with three main demands: eviction of the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL/ILV), to maintain CMPIO as an institution, and to recognize formally Indigenous schools. The government only signed off on their demands when the king and queen of Spain visited Mexico and wanted to see the famous Diego Rivera murals in the Ministry’s building. Fernando emphasized, however, that the struggle has come at a great cost with seven of their comrades being assassinated. CMPIO is a part of APPO, and Fernando emphasized that APPO did not just start last year but emerged out of years of struggle. An Indigenous concept of community allows people to resist the repression, exploitation, discrimination, racism, and poverty that they face. Both the Section 22 teachers union and APPO help sustain CMPIO’s efforts. Although APPO’s logo does not refer explicitly to Indigenous peoples, that concept is implicit with its references to community.  The CMPIO leaders acknowledged problems with APPO, including that it emerged too quickly which did not leave time to bring communities along with the process. This has complicated the organization’s decision-making processes. Teachers have two roles: to teach and to protest, but sometimes there is a lack fo logic between the two. Sometimes teachers replicate authoritarian systems in the classroom, and they need to break those patterns of dependency. This can be done through bringing empowering pedagogy into the communities. In addition, it is difficult to escape the government’s mechanisms of controls, particularly authoritarian caciques (chiefs) who maintain control over areas. Mexico, Fernando emphasized, is not interested in supporting education but rather privatizing the educational process in order to create a cheap labor force. The government is not interested in training us to think for ourselves or to become conscious of our reality. We need to study our history in order to become more conscious of it. Teachers play a critically central role in this process.

CEDICAM

We arose early on Tuesday morning to drive a couple hours north to Nochixtlan. We met with Jesús León, one of the leaders of CEDICAM (Center for the Integral Development of the Campesinos of the Mixteca Alta) at a school for training of small farmers that was still under construction. CEDICAM was formed in 1994 to deal with environmental issues of erosion, conservation of soil, and irrigation. Rather than embracing an explicit and overt political agenda, CEDICAM is a development organization that works with groups such as Bread for the World, Maryknoll, and World Neighbors. Nochixtlan has experienced some of the worst erosion in all of Mexico, largely from over grazing, plowing the topsoil, and destruction of forests for industrial production. Jesús described CEDICAM’s work over the past 10 years to conserve more than two thousand hectares of land through programs of sustainable agriculture. This includes a system of canals to prevent a run-off of rain water. An unexpected but welcome side affect of this program has been a recharging of the ground water supply. They also encourage intercropping and allowing land to lay fallow. Reforestation programs replant both pine and native trees. CEDICAM also encourages use of non-chemical fertilizers and pesticides. They are developing organic compost and worm farms as alternatives. A seed bank saves local seeds in order to break a dependency on genetically modified seeds. CEDICAM has a campaign with posters, flyers, and videos to defend local corn production against Monsanto. Vegetables are raised in greenhouses. The overall goal is one of encouraging autonomy, food sovereignty, and food security.  Jesús emphasized that the fundamental goal was one of capacitación, or popular education and training. The school where we met is designed to serve that purpose of teaching sustainable development. Value is placed on local products rather than assuming that items from the outside are better. Jesús also explained how neoliberal economic policies bring in cheap corn from the United States that undercuts local production and encourages migration out of the area and to the United States. This is a key issue, and they are working to sensitize young people to the possibilities of staying and working in the area. Somewhat ironically, the war in Guatemala in the 1980s brought refugees from there into Oaxaca and this project benefits from their knowledge and experience. Without the conflict in Guatemala, they would not have come. In this way, a good result came out of a bad situation. CEDICAM carries the name ‘campesino’ (peasant or small farmer), not Indigenous in its name, even though it would appear to outsiders that the area is a primarily Indigenous area. Jesús said that they debated naming the organzation “campesino y indígena” but thought that it would imply a division into two groups. Instead, they went with the broader and more comprehensive label “campesino.” Jesús noted that which academics tend to overstate the differences between campesinos and Indigenous, that they perhaps understated these distinctions. Nevertheless, with their milpas it is clear that farmers are following Indigenous practices.  After our discussion with Jesús, we drove two hours over increasingly rough roads to the misnamed Tres Lagunas, since only one of the three lagunas still survives. The community greeted us with glasses of coca-cola, and then served us lunch. Community leader Sosimo Santos López welcomed us with the statement that we were at full freedom to ask what we wanted, to take away both the good and the bad from the community. He described how they have been working with CEDICAM for the last several years in order to improve their lives. They work with Campesino to Campesino to reduce chemical usage and put these theories into practice. Sosimo pointed out that six years ago the area was all dessert, but with a reforestation program the land was making a come back. The community has prohibited hunting, and how wildlife is coming back. The community has experienced a strong out migration, to the point where the local school closed for a lack of students.  Domitla, a traditional healer, explained the strong–and in her mind negative–impact that family planning has had on the community because now there are fewer kids. Before giving birth was better with a midwife, but now many women go to clinics where they have bad experiences with western medicine that is too anxious to use C-sections. Domitla emphasized that women had better care before when they received it in their homes. After these discussions we visited a couple of farms. Walking across one field I noticed some pottery shards. One of the community members told me that some preliminary archaeological studies had been done in the region that pointed to a 2500 year-old village. Tres Lagunas is a community with a long and rich history that has only recently been disrupted with erosion and migration.

CIPO-RFM

This afternoon we met with Dolores Villalobo from the Consejo Indígena Popular de Oaxaca “Ricardo Flores Magón” (CIPO-RFM). She began the discussion with an explanation of who was Ricardo Flores Magón–an Indigenous person from Oaxaca who rose up against Porfirio Diáz in the Mexican Revolution. He was persecuted so fled into exile into the United States, but was imprisoned at Levenworth where he was executed. Franciso Madero offered him the vice presidency, but Flores Magón said he preferred jail to his government that was not of the people and who did not represent the change for which they had fought. Dolores said that Flores Magón is largely a forgotten person, but they want to reclaim his name because he was an Indigenous person who never gave up on his ideals. CIPO-RFM is continuing his struggle. CIPO-RFM was born in 1997 as an alliance of community organizations who opposed repression and fought for the rights of education, transportation, work, school, health, and other issues. They are rooted in a horizontal, assembly decision making model that rejects traditional political parties. They respect religious differences, rather than letting them divide the struggle. CIPO-RFM embraces ideas of autonomy, self determination, the rights to territory and natural resources, and the recuperation of cultures. Dolores was very critical of capitalism that has only served to underdevelop Indigenous communities. Electoral politics has also only proven to be an avenue for opportunists to gain power and wealth rather than working for the collective good.  Dolores indicated that CIPO-RFM shares a good deal of ideological affinity with the Zapatistas in Chiapas in terms of their struggles for respect, equality, real democracy, and territory. They also adhere to the Zapatistas’ Sixth Declaration. They seek to join all communities together into a unified struggle to overcome the capitalist system and to achieve a better future. Dolores emphasized that there is not only one way to achieve these goals, and there is a need to adapt to meet a changing reality. Other examples like Evo Morales in Bolivia or Hugo Chavez in Venezuela might be appropriate for their contexts and for their realities, but people need to build their own future in Oaxaca–and they are doing it as they go along. Dolores pointed to structural problems and individual problems, and the need to work on both levels. We have to rethink and challenge how we face these problems. The government treats Indigenous peoples as folkloric images rather than engaging the issues that they face. The San Andrés Accords was one example of how all political parties have rejected Indigenous demands. A problem with the capitalistic system is that it is based on resource extraction rather than helping people. We all have to do our own little bit to achieve a solution.

Pedro Matias

This morning we met with Pedro Matias, a journalist with 20 yrs of experience watching governmental abuses in Oaxaca. Last year´s teachers strike was only the last part of a long chain of events. He traced out a history of conflicts in which the government refused to act, leaving open the possibility for people to act with impunity and without fear of punishment. Oaxaca´s curent governor Ulisis Ruiz forms part of this history of institutional violence, including abusing and insulting communities by ignoring their needs. Because of a lack of government action, communities and individuals take justice into their own hands. Matias also traced out traditions of popular organzing. He broke the organizing efforts into three main categories: agricultural struggles for territory, social struggles for infrastructural needs, and community struggles for the rights of traditions and customs. APPO emerges as a broad based group comprised of 4 sectors: social organizations, teachers, human rights groups, and religious groups. It is not a homogenous organization, but incorporates many divergent interests. Indigenous communities have contributed 3 forms of organizing in Oaxaca. First is the tequio, voluntary work done in benefit of the community. Second is the guelaguetza which is a gift of pineapple, mango, bread, chocolate. The government has tried to turn this into a folkloric festival, and the communities have reacted against this. Finally is the assembly which contributes a model of consensus decision making processes.  Teachers move beyond their involvement in limited union issues to become more deeply involved in social struggles because of their close relations with communities. The Centro de Documentación de los Movimientos Armados (CeDeMA) lists 26 armed groups in Mexico, including 4 in Oaxaca. Matias noted that social movements tend to be better organized in Oaxaca than Chiapas. They have a longer history, and part of this history influenced the Zapatistas in Chiapas. The entire political class, including the leftwing PRD, tends to be discredited in Mexico. This political elite is willing to maintain themselves in power at any cost, and works to coopt political opponents. A current debate is whether or not to participate in the upcoming fall elections. Every hundred years Mexico seems to explode in revolution: in 1810 with Independence, 1910 with the Revolution, and people are now wondering what is in store for 2010.

Arrival

Arrived in Oaxaca after a long day of travel. I thought I would be able to join some of the delegation meetings today, but Mexicana changed my flight schedule so I missed everything. On the way from the airport to the hotel we not only passed a McDonalds, KFC, and Office Depot, but the road had an EXIT labeled just for them. It seemed so different from my first time in Mexico almost 25 yrs ago when there was so little foreign corporate presence. How much things have changed. I walked down to the Zocalo just to get a glimpse of a bit of the APPO presence there. Tomorrow there will be more opportunities to explore these issues. Right now I am tired and ready to go to bed.

Setting up blog

just setting up blog; still 3 trips away & not really thinking much about it yet.

| Marc Becker's Home Page

| marc@yachana.org |

|